Invest in research and development. When, how much and how? It is one of the workhorses of the business world, both in SMEs and in large corporations. But which of them invests the most in R&D?

In The Economist It can be read an interesting debate about whether large companies innovate more or less than small ones. It is known that growing without losing competitive advantages is the paradigm of balance, but many entrepreneurs and experts disagree when it comes to giving notice to large corporations and SMEs in the long-awaited innovation.

On his blog Calculated Exhuberance, Arpit Gupta focuses its criticism on Microsoft:

We don't want those who made money in the 90s to tell us now where to invest it. We want Microsoft shareholders to invest their millions in the Microsoft of the future.

Karl Smith, a professor at the University of North Carolina, points out problems in both types of organizations, also referring to the case of Microsoft and the situation in the United States:

Microsoft is stuck in its own red tape. It is more interested in continuing to exist than in increasing its benefits. The key to capitalism is destructive creation; big companies die as innovators enter the scene. However, modern companies guard most of their profits suspiciously to avoid their own death. This is an economic loss. Bad for investors, and bad for the United States.

Michael Lind, an expert writer in economics, believes that large companies are not compensated for investing in R&D in a market where competitors take advantage of the advances of others:

In a competitive market, undercapitalized companies have no money to invest in R&D, and large companies find little incentive to achieve technological advances that they will have to share with their competitors.

Ata The Economist that the justification for intellectual property protection seems to be the fact that companies need a period of monopoly benefits to justify investment in a new product or technology.

In another article, The Economist talks about the IBM situation.

The company appears to be suffering from diseases similar to those of IBM in 1993, after Lou Gerstner was hired to relaunch it. Among them, the arrogance that comes from feeling like they dominate an area of the market, or the internal struggles that hinder renewal. For example, the cloud computing department has to deal with one that seems to want computing to stay on the desktop for as long as possible to maximize its own revenues.

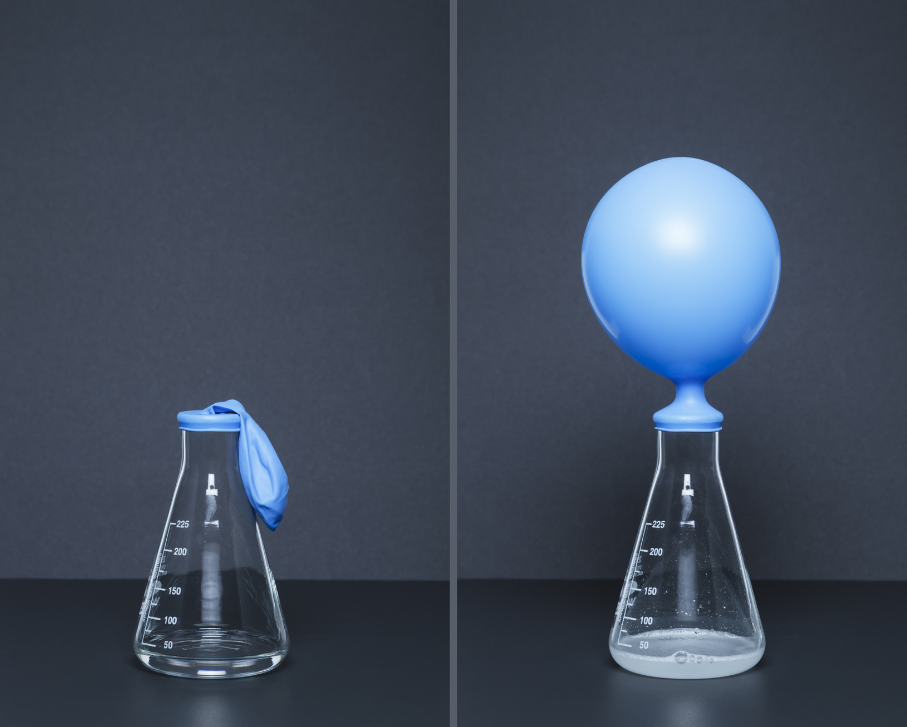

Finally, we want to highlight the words of Guy Kawasaki (formerly Apple) in a recent interview with Javier Megías, consultant and advisor to the European Commission:

Apple is a perfect example of a company that has stayed young (...). My advice is that companies should remember why customers trust you. For example, an ice factory in the 1930s offered the same service as a refrigerator company in the 1950s: practicality and cleanliness. The ice factory business wasn't really the centralized freezing of water. Their business was practicality and cleanliness, and the industry should have jumped on the bandwagon of changes brought by refrigerators. But hardly any company did it, because they thought of themselves as centralized water freezing factories. The other important thing to remember is that there are always, somewhere, two guys in a garage planning your disappearance. Either you are ahead of them, or they will succeed.