The techniques used to value companies with stabilized business models do not always work for young high-growth companies, which often have not yet yielded benefits.

How is a startup valued

The intrinsic valuation of a company is based on the performance of 4 components:

1. Cash flows from existing assets

2. The expected growth derived from new investments and the improvement of the efficiency of existing assets.

3. Discount rates are a function of business risk.

4. The forecast of when the company will become a stable growth company.

The most common technique for valuing companies with stabilized business models is to discount free cash flows. The theory behind this definition is that an asset is worth the cash flow it can generate over time, discounted from its current value, plus the terminal value it has at the end of its useful life, also discounted at the present.

As we can see, this method requires that we be able to make a financial projection that is as rigorous as possible, based on known data from the company's past as well as its extrapolation to the future based on what we can presume will happen later. Among the different factors involved in an analysis of this type, there are two that are especially important: 1) The discount rate; and 2) the terminal value. Given the difficulty in estimating many of the variables necessary to make an accurate financial projection, this method is not the most suitable for use in startups, but before we start to review the ones most used specifically for this type of company, it is important and useful to know it and understand the logic behind it.

Discount Rate

In companies that are listed on the stock market and that have historical data, the discount rate is calculated based on a model called “Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). Within the framework of the CAPM, the determination of the rate that we have to use for the discount of free cash flows is based on the following formula:

Where:

- Ks is the expected discount rate of cash flows

- Rf is the discount rate of a risk-free product (usually the 10-year US bond is taken).

- E (rm) is the discount rate of a global portfolio of stocks. The S&P500 is usually taken

- Beta: represents the volatility of a stock compared to that of the market in general, for example the S&P500 index. To calculate beta, the following determinants must be taken into account:

- The type of business of the company: The more sensitive a business is to market changes, the higher its beta.

- Degree of operating leverage: Depending on a company's cost structure (ratio between fixed costs and total costs), the higher the fixed costs in relation to total costs, the higher the beta.

- Financial Leverage: An increase in financial leverage increases a company's beta.

Terminal Value

On the other hand, terminal value is defined as the value of the business beyond the forecast period in which future cash flow flows can be estimated. In this sense, the life of a company is usually divided into two parts: a “discrete” period, which varies between 3 and 10 years, in which the evolution of the different variables (sales, costs, market growth, market share that can be captured by the company, etc.) can be estimated more or less reasonably, and another “infinite” period that captures the future value of the cash flows expected by the company in the rest of its infinite life, after the discrete period. To calculate the end value of a company, there is the following formula: VtT = cFn+1/(Ks — g)

Where:

- CFn+1 It is the cash flow for the first year after the discrete period

- Ks It is the discount rate of cash flows, and for this purpose the same one that was estimated correct for the discrete period is used

- g It is the long-term growth rate of the business

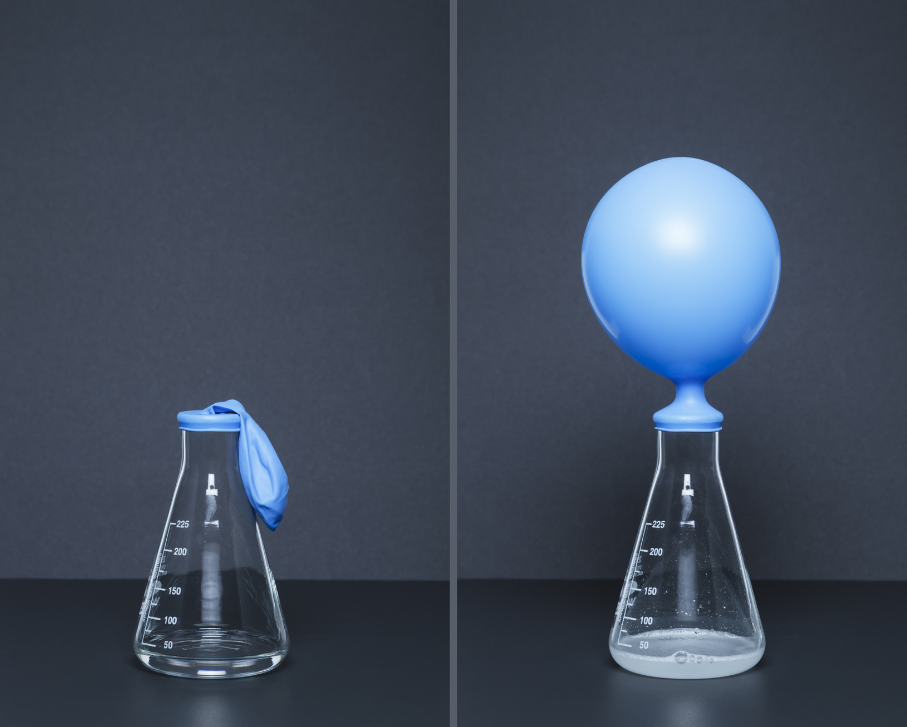

Challenges when it comes to evaluating Startups

A simple look at the two previous formulas can already give us an idea of the difficulty (or perhaps rather the impossibility) of applying this model to startups. Startups are characterized by having very early business ideas, with business models that often have to be put to the test by force of trial and error, suffer from stable metrics over time, and - as we said before - most of the time they have not yet shown the capacity to generate profits, much less to generate positive free cash flows. Therefore, in addition to the difficulty (and arbitrariness) involved in trying to estimate many of the variables necessary to be able to make a more or less reasonable projection of the future evolution of cash flows, calculating the discount rate at which they should be discounted to estimate a net present value is impossible, since the company is not listed on the market and therefore it is directly impossible to calculate its beta. In addition, early-stage startups rely heavily on investment from founders, friends or family, and later on business angels or venture capitals, whose expected returns are much higher than what an investor in the stock market can expect.

So what?

Even when we talk about startups, due to their scarce track record, the concept of free cash flows has often not yet materialized... And yet, despite all these challenges, it is necessary to find valid ways to value these types of companies. What alternative methods can we use then?

1. Venture Capital Approach

The first thing to consider when we talk about a startup with little history is that it is better to rely on the income variable than on the benefits variable. This is because the variable income or sales is much more difficult to manipulate than the variable profits or free cash flows. The Venture Capital Approach, put in very simple terms, is structured in 4 steps:

- The first step, provided that the amount of investment needed has already been defined, is to estimate the expected revenues of the company, it consists of estimating the probable sale value (Exit Value) of a startup over a period of 5 to 7 years. For practical purposes and to give a concrete example, let's consider that we want to evaluate a Software as a Service (SaaS) startup and that we have 7-year projections.

- The next step is to find the average multiple at which the shares of companies in the sector are bought and sold. In the case of SaaS companies, for example, we can use the SaaS Capital website: https://www.saas-capital.com. Since the index we obtain here is for listed companies (and therefore with high liquidity), we must adjust this index to be able to apply it to private companies, with much lower liquidity. This setting depends on many factors, but is usually in the region of 30% down. Multiplying the company's estimated revenues for year 7, by the adjusted multiplier, we'll get what the company will be worth seven years from now.

- Finally, we must now discount this value, which, as we said, would correspond to year 7. To do this, we must first determine the most appropriate discount rate. This will depend on the expectations of the VC as well as the company's stage of development. In general, this discount rate is usually in the range of 40%-60%.

2. Multiples

The multiple method is a simpler variant of the Venture Capital Approach. In this case, we simply take the company's ARR (Annual Recurrent Revenue) and apply the corresponding multiple (which can be an average multiple corresponding to several recent M&A transactions with companies similar to the one we are looking to value). Again, we will rely on multiples of income to avoid errors derived from manipulations in the calculation of benefits and we will adjust for liquidity depending on the source from which we extract the multiple. If we have information about transactions from private companies, we will not have to make any adjustments, and on the other hand, if we work with multiples of transactions from public companies, we will have to make an adjustment similar to that indicated in the previous method.

3. Berkus method

For pre-revenue startups, there are approaches such as Berkus, also called the Scorecard Method. It is a highly arbitrary approach, as will be seen, and although it can be refined and refined, it will remain arbitrary... In the Berkus method, a series of dimensions are defined, which are the company's value “drivers”, to which a fixed value, say 500K€, is assigned to each dimension. Then it is considered how much of each dimension the company complies with. The sum of the weighted values will be the total value of the startup. For example:

- Dimension 1: Innovative Idea

- Dimension 2: Quality and degree of progress of the prototype created

- Dimension 3: Quality of the entrepreneurial team

- Dimension 4: Strategic Relationships

- Dimension 5: Level of rollout progress/sales achieved

If the company complied with all these dimensions at 100%, its value would be 2.5 M€... But, if, for example, dimensions 2 and 5 only met them at 80%, then the valuation would drop to 2.3 M€.If you have questions about how they apply these valuation methods to your particular startup, don't hesitate to contact us so that we can help you with it.